In this series, I am not going to touch on Indo-China where France’s rule in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam was barbarous and where its missionary efforts had usually, but not always, met with widespread aversion; nor the aftermath of the monstrous eight-year bombing campaign over Laos, the disastrous American follies in the Vietnam War and the consequent genocide in Cambodia. These are topics for a much longer historical exploration. In the meantime, over the next three episodes I look south and west to Malaysia and Indonesia where all the evidence points to life for gay men becoming considerably more difficult.

South of the Thai border, changes also occurred in gay life and customs as a result of conquest and the advent of new religions, but far more slowly. Trying to work it all out is rather like peeling layers from an onion. As far as the former British Colony of Malaya is concerned, the initial temptation is to blame it all on the sledgehammer of the dreaded British 1861 law.

Long before the British, though, there were waves of other foreign visitors who, whilst not invaders, had a tendency to stay on for many hundreds of years. Much of South East Asia had come under Hindu influence as early as the first century AD. Trade was the primary motive. Inevitably religion followed and in much of this part of the continent Buddhist/Hindu beliefs were to bring a lasting unity to the region.

For centuries Arabs were also forging trade routes between South East Asia and the Middle East. Yet even after the founding of Islam in the early seventh century there was no immediate conversion of local rulers. Indeed, by 1200 AD most of the region was still part of the Buddhist Srivijaya state based in Sumatra. It was only as Srivijaya started to decline that Islam was adopted, first in Aceh in present day Indonesia. Trade routes carried the religion westwards to Java and beyond, and north to much of present-day Malaysia and Borneo.

Only Bali remained as a small enclave with its own brand of Hinduism. And only there did it remain perfectly natural to appear naked in public without concern about who might be watching. I have very happy memories of visits in the early 1980s. I always stayed in a small hotel with no electricity on a hillside outside a very undeveloped Ubud. Late every afternoon it was common to see boys and men of all ages make their way to the streams and water spigots, undress and proceed to shower. The sight of those slim, glistening, naked brown bodies was a perfect highlight of each day.

Bali' Kecak Dance - copyright Hello Travel

Once about to fly to Jakarta in a Garuda DC10, I even saw a young worker strip naked and bathe himself in a small stream between the taxiway and the runway. When I visited the artist Antonio Blanco whose studio was close by my hotel, all the girls working for him were unashamedly topless. A degree of public nudity was therefore still relatively common.

I have little understanding of Hinduism and so cannot comment much on its beliefs as far as homosexuality is concerned. We know from the sexually explicit carvings on the temples in India’s Khajuraho (once described as a “catalogue of desire” that includes men and women contorting their bodies in all but impossible sexual positions) and in other parts of the sub-continent, that eroticism played a major part in Hindu sexual life. I have seen similar temples in Bhaktapur and Patan in the Kathmandu valley with a variety of fascinating couplings. But if I posted any of my photos here, they would be quickly withdrawn, so I must leave the possibilities to your imagination.

The entrance to Patan's Durbar Square

Prior to the 13th century in India, sex was taught as a subject in formal education and nudity is prominent in painting and sculpture. Reference to homosexual behaviour is found in some sacred literature. We also know that when Sir Charles Napier annexed Sindh Province for the British, the region around Karachi in present day Pakistan, he was quite horrified to discover male brothels with boys and eunochs.

As for Islam, in the early 1970s writer Charles Allen interviewed a group of Britons who had worked in India in the early 20th century. “Plain Tales from the Raj” offers an often amusing if somewhat racist glimpse into colonial life. One episode recounts the visit of a British Tax Inspector to check the accounts of the fabulously wealthy Nizam of Hyderabad, the largest and richest of India’s Princely states located in the centre of the country.

It was also one of the most sexually liberal and it so happened this particular Nizam was very gay. As the Inspector arrived, he was met by an honour guard of exceptionally handsome young men. Greeted by the Nizam, he was invited to rest after his long journey in a lavishly decorated suite. After a bath and about to take a nap, he was horrified to find a young boy under the sheets. “Get out of here this instant,” the civil servant shouted. The poor boy was unsure what to do. “But I am here for you,” he said plaintively. “I’m your present!” Even more outraged, the Inspector was about to call for a guard when the boy slowly pulled a long silk scarf out of his derrière. “See, I’m clean!”

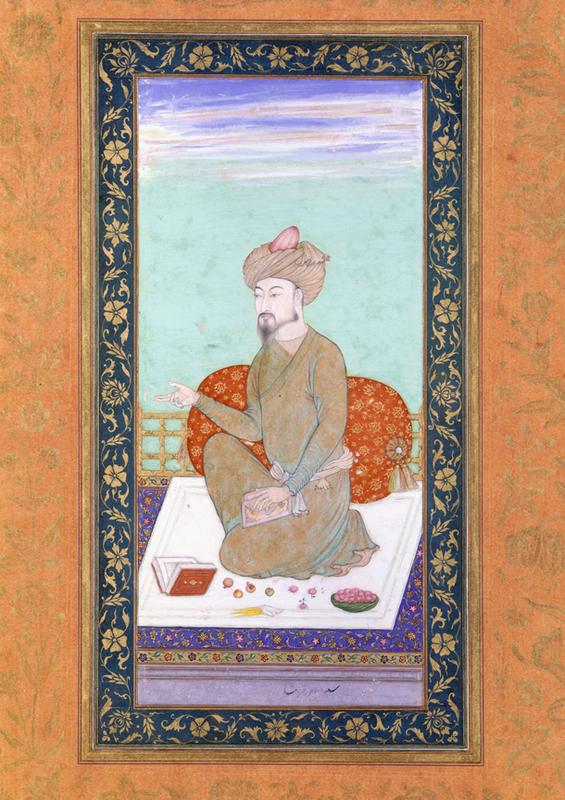

The title “Nizam” comes from Arabic and was introduced to India by Babur, the first of the Muslim Mughal Emperors who led his forces into North India in 1526. The Mughals were partly descended from Persian ancestry and the name Babur is assumed to refer to the Persian word for tiger. A direct descendant of Tamerlane the Great, Babur himself was partial to what he terms in his autobiography “boy-love” despite adhering to Islam. Babur was indifferent about his wife and much preferred the company of boys and young men, although it is not clear today whether such liaisons were sexual or more that of a mentor in an emotional sense.

Portrait of Babur

So just as dicks were disappearing from male nude statues in Europe, an Islamic reign was being established through force and diplomacy on parts of the Indian subcontinent. By then, Islam had also spread throughout Sumatra and the Malay States, but in a far more peaceful manner. Conversion was voluntary and the local Islamic leaders were keen to exhibit a tolerance for coexistence with local Hindu/Buddhist customs and rituals. Thus within a few centuries a majority of peoples in the region came to worship Islam.

But then, ominously, larger sailing ships appeared on the horizon. They soon made it clear they were not friendly.